Could Tāmaki Makaurau decide the next election?

You have 12 months left to prepare for the possibility of a Prime Minister Simon Bridges. It’s a terrifying thought — well, for progressives — but it seems increasingly likely the National Party leader is going to push the Labour-led government hard. Last night's 1News Colmar Brunton poll signals National is settling in at 46%*. This is the John Key sweet spot. With an assist from David Seymour’s Act Party, or even Winston Peters’ New Zealand First, the sixth National government could take office in 2020. So long, Jacinda and Clarke, and thanks for all the fish.

But how plausible is that, really? The Prime Minister’s net approval ratings are spectacular, and her government is sitting on a $7.5 billion surplus. If Finance Minister Grant Robertson is in a reformist mood — or, rather, a campaigning mood — he could arrange an election-year lolly scramble, allocating billions more to health, education and housing. Few people would complain (other than Bridges), but even if voters are reluctant to back further government spending, the Labour, New Zealand First and Green parties still enjoy a combined six-seat lead over the Opposition in Parliament. How likely is it National can close the gap?

The trouble with this reading is it obscures how close-run the last election really was. Sure, the Labour-led government commands that lead on the Opposition, but it only governs with a parliamentary majority of three (63 seats in a 120-seat chamber). If you recall the results on election night, the Bill English-led National Party and its Epsom surrogate were only two seats away from securing the numbers to form a government. If the Māori Party had made it back with their two seats, perhaps this column would open with a different hypothetical: you have 12 months to prepare for the possibility of a Prime Minister Jacinda Ardern.

This is another way of saying the Māori electorates matter. Andrew Little’s former chief of staff, the old-time union strategist Matt McCarten, knew it as early as 2016, deciding on a strategy to target Māori Party co-leader Te Ururoa Flavell in the Waiariki electorate and United Future’s Peter Dunne in Ōhāriu. Hard heads in Labour understood National’s base (that magic 47%) was more or less immovable, and the key wasn’t necessarily a dramatic swing in the party vote. The best bet in 2017 was taking out the then government’s support partners. It goes without saying, but for the record: it worked.

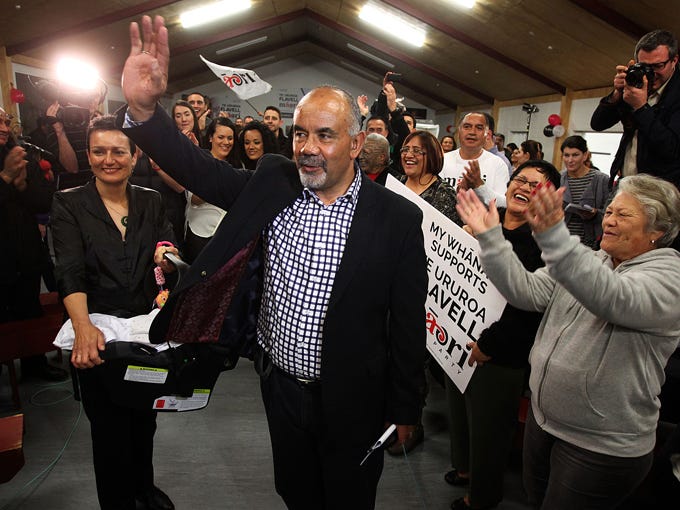

Labour ran hard in the Māori electorates. Its Ikaroa-Rāwhiti MP, Meka Whaitiri, ripped into Flavell for proposing wholesale changes to Māori land law. His opponent in Waiariki, Labour’s Tamati Coffey, was a door-knocking machine. In an early year set-piece, Little told RNZ the Māori Party wasn’t a “kaupapa Māori party”. The targeting was brutally effective. Coffey took Waiariki with a comfortable majority. The morning after the election, Flavell, in a signal of where his political priorities and loyalties were, told media English “deserved another three years”. In his valedictory speech, the outgoing Prime Minister described Flavell as a “friend” and spoke affectionately about the partnership between their two parties.

But the special votes eventually put the prospect of another National-Act-Māori Party government just out of reach. Flavell’s loss does indicate, though, just how close it came — and just how important the Māori electorates are to the outcome in 2020. Throughout the 20th century there were several elections where the Māori electorates were crucial, including in 1946 and 1957 when Labour’s Māori MPs took them over the line. It’s not implausible to imagine the same in 2020.

But which Māori electorate is crucial to the election outcome? Only one. Auckland’s Tāmaki Makaurau. The government’s dithering over Ihumātao means seat holder and Whānau Ora Minister Peeni Henare is at risk. Compounding his problems are his government’s spectacular failure to deliver in housing — an acute issue in his electorate — and a vocal campaign against his policies for Whānau Ora. Critics are cornering him with two issue accusations: one, there isn’t enough money; and two, the money that does exist isn’t all going to the existing “commissioning agencies” (who commission Whānau Ora “outcomes”).

This is an unusual position for Labour’s Māori MPs. For the past 10 years, they were the insurgent force in politics, securing big wins against the Māori Party. But they are learning what every government MP eventually finds out: you’re not really running against your opponents, you run against your record. And Labour’s is, well, fine. A partisan might go as far as saying it’s very good, but we’re far from the transformation we were promised in 2017. For Māori voters at the bottom of all the wrong social and economic statistics, this isn’t just a letdown: it’s disillusioning.

Commentators are beginning to sense an upset is possible. There’s blood in the water. Sharks are circling. There are rumours John Tamihere may have a crack. Can he really win it, though, especially off the back of a landslide mayoral loss? I rate his chances. Pākehā know Tamihere, if at all, for “front bums” and his long list of intolerable comments. But Māori know him as the bloke who put their aunty in a home, found a job for their cousin, and played in the backline with their old man. This is why he’s viable, at least in Tāmaki Makaurau.

This piles the pressure on Labour. It’s important, for re-election no less, that Māori in the party are given the greatest control possible over their campaign. Māori must occupy senior positions in the party, giving them the mana to make big decisions and big reforms. And support must go up around Henare. Anything less and the country might get a Prime Minister Simon Bridges.

*The October poll referenced in the print version of this story saw National at 47% and has been updated to run online.